Ben Hills

Her bare black feet are cracked and calloused and covered in the ochre dust of the Kimberley. She is stooped so low that her eyes are curtained by her long white eyebrows. She is wearing a blouse and skirt that have seen better days, and on her head is a floppy cloth bonnet.

Meet ‘Daisy’ Loongkoonan, one of Australia’s most famous artists and almost certainly the oldest — at the grand age of 105. Her gaudy canvasses, bright with coloured dots depicting the flora and fauna of this remote reach of Western Australia have been exhibited in every capital in the country, have wowed the critics in France and the United States, and sell for up to $12,000.

And this is how she lives. She is sitting on a plastic chair on the verandah of her home, a corrugated iron cottage with no TV or telephone which her niece and carer, Annie Milgin, calls “this old place, nearly falling down”. Stray brown dogs dart around her legs as she reminisces about her childhood as a station hand in the first decades of the last century.

There is little sign of the scores of thousands of dollars she must have earned over the years since she was “discovered” in her 90s, and went on to enter – and win – several of the country’s most prestigious art prizes, with her work placed on sale in Paris, Perth and Melbourne.

Foreign minister Julie Bishop and Henry Skerritt

(Photograph courtesy of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade)

This is not the Loongkoonan the world knows from TV documentaries and effusive magazine profiles, dolled up for the cameras in a fancy hat and Sunday-best dress, with a paint-brush in her hand. Not the Loongkoonan who, just a few months earlier, had a retrospective exhibition opened at the Australian Embassy in Washington DC by our foreign minister, Julie Bishop.

So what became of all her money? And why did she stop painting? It is a sorry story of fraud, “humbug”, elder abuse and theft.

These days Loongkoonan lives out her life in the tiny settlement of Jarlmadangah Burru. It’s only 260-odd kilometres from Broome’s glittering Cable Beach, where tourists caper on camels as the sun sinks into the Indian Ocean, but it’s three hours by car – the last bone-rattling stretch over a corrugated dirt road deep with drifts of bulldust that you need a four-wheel-drive to navigate.

The craggy red ridges of the Grant Ranges form the backdrop to the settlement, and the lower reaches of the Fitzroy River – where Loongkoonan and her ancestors once fished for barramundi – are a couple of kilometres away. The spinifex scrub is dry and dusty, punctuated by the bloated trunks of boab trees and head-high termite mounds like huge piles of dinosaur dung.

I have been invited to meet Loongkoonan at Jarlmadangah by Annie Milgin, but Annie has taken herself to hospital in nearby Derby with a nasty boil on her neck, and so I arrive unexpected. At first glance the place is deserted – this is a ‘dry’ community and the Monday I visit almost every man is away in Broome or Derby. It is a village inhabited by women and children.

Eventually I find Loongkoonan, and another niece, Hilda Gray, agrees to help with the interview. In her extreme old age, Loongkoonan is losing her ‘Kimberley English’ and reverting to her native Nyikina – she is one of the last living speakers of this ancient, endangered language.

She is sitting with her head bowed towards her chest, speaking so softly Hilda bends in to hear her. Her hands are now so feeble that she struggles to unwrap a gift I have brought her, wrapped in tissue paper, and eventually surrenders it to Hilda to open for her.

With a little prompting, she explains that when she was born here, on a vast property covering 133,000 hectares named Mt Anderson Station, no one recorded Aboriginal births, deaths or marriages. In fact when she was a child they used to be numbered among the livestock when a property was listed for sale.

Her people worked for no pay, just a shirt, pants and a pair of boots each year, and rations of flour, sugar and chewing tobacco. It was a rough life in other ways, too – on the outskirts of Derby is a ghoulish tourist attraction: an ancient, huge, hollow boab called the Prison Tree where it’s said that Aborigines were penned on their way to court.

So no-one can be certain exactly how old she is. Her presumed birth date of 1910 – when Alfred Deakin was prime minister, Harry Houdini flew the first plane over Australia and the Royal Australian Navy was created – is calculated by reference to people and events Loongkoonan remembers, counting back from what is referred to in the Kimberley as “the Japanese war”.

Nor does anyone know to what to attribute her long life, when so many of the graves in the local cemetery where she herself will be laid to rest one day are marked with white wooden crosses bearing the names and dates of children.

“No drinking,” translates Hilda. “No smoking. Eat good bush tucker, barni (goanna), things like that.”

No vices at all?

“Old girl, she like tobacco. Chewing tobacco like they got in the old days,” she chuckles.

She never attended school – Loongkoonan cannot read or write – and was put to work as a child, doing housework for the station manager, and later cooking, and riding a horse to round up the sheep and cattle.

…a custodian of the ancient Nyikina heritage, a living library of the language, the customs and the culture.

During the rainy season – which can stretch from December to February when the monsoon can dump metres of rain on the arid hinterland – she used to go on “footwalking” holidays with her kin, learning about the lie of the land, the bush tucker that features in her paintings, the ceremonies and the sacred sites.

She is regarded as a custodian of the ancient Nyikina heritage, a living library of the language, the customs and the culture. She knows how to get the ‘glue’ from spinifex bushes to fix spearheads to shafts, how to catch freshwater crocodiles (“You gotta hold the mouth shut”), how to cook a turtle and carve a coolamon, an Indigenous carrying vessel.

In the wake of the Wave Hill “strike” of the 1960s, when Aboriginal workers won the right to equal pay and were turned off stations across northern Australia, Loongkoonan moved to Broome and then to Derby. Her family insists that she “wore out three husbands” but the day I ask her she can only remember one of them. She had no children.

By the mid-1990s, when Kevin Shaw began to notice her knocking around the streets of Broome, she would have been in her 80s. Shaw is an anthropologist who at the time was the administrator of the Aboriginal Heritage Act in the Kimberley – in charge of cataloguing significant sites.

“She was on the pensioner scrap-heap,” he says bluntly. “She and her husband Julga were living by visiting, as they say. Visiting friends or family. She was homeless; she was living on the generosity of other people; she had no money; she spoke Kimberley blackfella English, not the lingua franca of survival.”

Kevin had no idea at the time, but by a series of improbable twists of fate he was about to change Loongkoonan’s life…. and change our ideas about Aboriginal art.

A charitable man, Kevin had taken in an elderly Aboriginal artist named Ngarra to live with him. Kevin wondered whether there was a market for the vivid abstracts and spooky spirit paintings he was producing. He asked an old friend.

Years earlier, while he was living in Perth and studying anthropology at Charles Sturt University, he had got to know his doctor, Diane Mossenson, who had since had a mid-life career change and opened art galleries in the inner-city suburbs of Subiaco in Perth and Carlton in Melbourne.

One day Kevin arrived with a bundle of Ngarra’s paintings under his arm to see what she thought of them – and Diane was hooked. She agreed to act as his agent.

Fast forward a few years. Loongkoonan, now in her 90s, has moved to Derby, her husband has died, and she is being looked after by a niece, Margie Cowie. Nearby, another friend of Kevin’s, a local tradesman named Eugene O’Doherty, has gathered together a small group of Aboriginal artists and made a studio for them in his Colorbond home on a bush block a few kilometres out of town.

Margie is keen to take a fulltime job, but worries how her elderly aunt will cope without her. Kevin comes to the rescue. He makes the introduction, and Loongkoonan joins Omborrin, Lucy Ward, Kitpi and other artists in the group, taking a paint-brush in her hand for the first time at the age of 94.

“They liked it there because it was peaceful,” says Kevin. “They could get away from the back streets of Broome and Derby with the drinking and the drug abuse and people screaming at each other day and night.”

Every day Eugene would do a pick-up run, collecting the painters from wherever they were staying and driving them to his property, which became known, rather grandly, as the Manambarra Aboriginal Artists’ Studio. Diane Mossenson sent them the acrylic paint, the brushes and the canvases, and Kevin cooked their meals and drove them to the doctor if they needed medical attention.

“Loongkoonan was a natural. No one taught her, she just took off.”

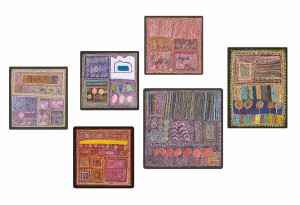

“Loongkoonan was a natural,” he says. “No one taught her, she just took off.” Her early paintings were rather crude and unformed, but she quickly developed a unique and ideosyncratic style of vividly-coloured dot painting, quite different from the Wandjina spirit figures popularised by artists such as Lily Karadada or the sombre bushscapes of Rover Thomas.

Henry Skerritt, an art historian and curator who specialises in Aboriginal painting, was the manager of Diane Mossenson’s gallery in Carlton in 2004. “In December we were just about to wrap up for Christmas when a roll of canvases arrived,” he told me. “They were the very first works by an old lady that none of us knew anything about: Daisy Loongkoonan.

“We picked the best 25 and exhibited them in a show called River Stories that opened the following February. I worked at the gallery until 2009 and watched Loongkoonan’s work go from strength to strength.

“The early paintings are scratchy and rough. She hadn’t quite worked out how to apply paint to the canvas… but within about 12 months she had refined her technique and developed her mature style, offsetting light and dark coloured dots to get the very organic shimmer that characterises her work.”

Diane Mossenson remembers the thrill when a customer, a member of an artists’ group, saw one of Loongkoonan’s early paintings hanging on the gallery wall and bought it – for $990. Her first sale… and there would be many more to follow.

Once she got the hang of things Loongkoonan proved to be astonishingly productive. Stooped over her canvases, with her face almost touching the wet paint, she produced 372 paintings in about five years, more than one a week, each numbered on the back by Kevin.

Just one year after she started painting, Loongkoonan’s work was placed in an exhibition at the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne. Over the following seven years she was hung in more than 60 exhibitions in every capital city and a host of regional centres, from Bendigo to the Gold Coast, Geelong to McLaren Vale, Taree to Alice Springs.

One work was entered in the prestigious Wynne Prize in Sydney, little brother of the Archibald Prize for portraiture. In 2006 and 2007 she won first prize in the Redland Art Awards in Queensland, the Drawing Together art award staged by the National Archives in Canberra, and the Willoughby prize for painting and mixed media in NSW. Loongkoonan was on her way to fame, if not fortune.

In her 90s she took her first plane trips, to Perth, Brisbane and Melbourne to see her exhibitions. When she got to Sydney she accosted Eugene, who had accompanied her, demanding to visit “the jetty”. He finally worked out that she meant the Harbour Bridge, which she had seen on TV blazing with New Year’s fireworks, and the following day he took her for a sight-seeing ferry ride on the harbour.

With her widening circle of fame, the price of Loongkoonan’s work crept higher and higher. From $990 for a small, early work, to a range of $3000 to $7000 for her more assured and accomplished pieces. Today, hanging on the wall of Diane Mossenson’s Subiaco gallery are two large paintings, perhaps 80 centimetres square, which carry a price tag of $12,000 each, towards the top end of contemporary Aboriginal art prices.

Dr Mossenson is rather coy when asked the total value of Loongkoonan’s works. She says that ‘about half’ the 372 paintings have been sold – some to her own family collection – but baulks at putting a value of over $100,000 on them, net of her own commission (which typically runs to about 30 per cent of the value of the painting) and payments for art materials and for Eugene O’Doherty’s time.

But she admits that she became concerned that Loongkoonan – by now approaching 100 – was not capable of looking after her new-found money, given her illiteracy and the fact that she had never had more than her pension payments to handle.

“When I knew her no one wanted to come near her – she was just an old woman living on the street, destitute. But as soon as she got a bit of money the scumbags descended on her like blowflies.”

Kevin Shaw puts it more crudely: “When I knew her no-one wanted to come near her – she was just an old woman living on the street, destitute. But as soon as she got a bit of money the scumbags descended on her like blowflies.”

For Diane Mossenson it came to a head in 2007 when Loongkoonan won the Drawing Together prize, which carried $10,000 in prize money. A long-lost nephew named Brian – now deceased – journeyed the 2400 kilometres from Perth to take control of Loongkoonan and her affairs, cutting her niece Margie out of the picture and installing her in a house he rented.

The money began to flow out of Loongkoonan’s bank account – and, perhaps worse, he chased away Kevin and prevented her from joining her friends at the Manambarra studio. The artworks stopped arriving at the Mossenson galleries.

Her niece Annie confirms the story: “She was locked up in the house looking at the four walls all day. They (Brian and his friends, who had also moved in) wouldn’t let her go out, wouldn’t let her do her painting. All they wanted was money from her. They was just humbugging her.”

Eventually the money was gone – as were three cars which had been bought to transport Loongkoonan around, but which either disappeared or mysteriously had the registration transferred into someone else’s name. The relatives moved on, and Loongkoonan was destined to be committed to the Numbala Nunga nursing home in Derby to see out her days – a fate she dreaded.

Alarmed, Margie made contact with her cousin Annie at Jarlmadangah where she lived, and they plotted a rescue operation. “I was really angry when I heard what they did,” says Annie. “I felt really sorry for the old girl, so I brought her here. I rescued her from those people who had been doing this dirty work to her.”

And so Loongkoonan came to live with Annie, away from O’Doherty’s artists’ group where paint and canvas was readily available. The price of getting away from the people who would exploit her meant giving up her art.

Those pictures of her daubing away at a painting which you may have seen on TV, like the flash clothes she was wearing, were put on for the camera. Loongkoonan has not painted a thing for four or five years. “I’m finished now,” she says, in her quiet, halting English. “It’s all done.”

But if Annie thought her aunt would be safe out on that remote settlement she was wrong. Not long after she moved to Jarlmadangah, Loongkoonan was driven in to the bank in Derby to access her money.

“The bank account was empty,” says Annie. “Someone took her money by telling a lie.” That someone had attended the Centrelink office in Mandurah, 2500 kilometres away, posing as Loongkoonan’s carer, and had her pension diverted into their account.

Nowadays things are on a more even keel. More money than ever is coming in since, earlier this year, Henry Skerritt curated a special retrospective exhibition of Loongkoonan’s work, which had been collected by Diane Mossenson, entitled Yimardoowarra: Artist of the River. It was on display at the Australian Embassy in Washington DC, and is now taking pride of place at the University of Virginia’s Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection in Charlottesville.

The exhibition generated a rave review of the art and the ancient artist in The New York Times, and since it opened Diane Mossenson has been deluged with emails from overseas. She put the price of Loongkoonan’s large paintings up to $12,000, and has since sold two to Stonnington Council in Melbourne.

Even in the Aladdin’s cave of Aboriginal art that is the Mossenson Gallery in Subiaco, her work stands out. There is an extraordinary collection here of, literally, thousands of works. At the back of the gallery is a thicket of carved totem poles, huge Papunya Tula paintings from the Western Desert parade along one wall, there are carved aligators and coolamons, and a nest of blue and green ‘ghost nets’ from Moa Island in the Torres Strait.

But there is no mistaking the vivid, grid-pattern work of Loongkoonan, depicting abstract scenes from her home country – gum trees, coolamons, a boomerang, the blue of the Fitzroy River, the green of the bush, the ochre of the soil. She belongs to no “school”. Her work is unique.

Up north in Jarlmadangah things have also settled down. Annie says that she now has a “power of eternity” (sic) over her aunt’s affairs, and looks after what is left of the money. Diane Mossenson has established a special account for Loongkoonan, and when Annie thinks she needs something – for instance, the other day she wanted a freezer – she goes to the home appliance store in Derby to price it, and Diane transfers the money directly to the store.

“She wants to go fishing again,” says Annie. “Catch some barramundi and some catfish. Maybe we also get a goanna.”

Eugene O’Doherty has been delegated to find her yet another car, settling on a second-hand four-wheel-drive Holden Colorado, capable of handling the rugged conditions at Jarlmadangah. “She wants to go fishing again,” says Annie. “Catch some barramundi and some catfish. Maybe we also get a goanna.”

But still the humbuggers keep trying. Diane Mossenson tells me about a message she got from the Art Gallery of South Australia, where an exhibition of Loongkoonan’s art was staged earlier this year for the Adelaide Biennial.

“They wrote to me saying that a group of Aboriginal people had come in to see the paintings, and they were crying because they said they were painted by a long-lost relative,” she laughs. “They were going to be evicted from their home on Tuesday, and they wanted to know how to get in touch with Loongkoonan.”

Needless to say, the address was not passed on.

As for Annie, she says she has no idea how much of Loongkoonan’s money is left after all the humbugging. “I just wish we could get a better house for the old girl… a better bed … maybe TV,” she dreams.

Publishing Info

Pub: SBS Online

Pub date: June 2015