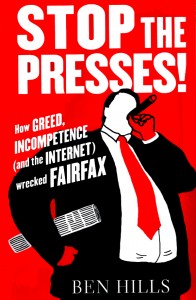

Once the mighty empire of John Fairfax dominated the Australian media landscape, but in recent years it has careened from disaster to disaster. Its famous advertising ‘rivers of gold’ have dried up. Most of its best and brightest journalists have been forced into redundancy. Its strategies for keeping up with the digital age have made it a laughing stock. Its management decisions have yielded moments of high drama and low farce. How could it all have gone so wrong?

Ben Hills takes readers on a lively ride through Fairfax’s slow and painful decline. He introduces the characters who have brought the place to its knees, from a stream of overpaid and under-qualified directors and executives to the predatory moguls circling, to the warring family members who guttes their own inheritance. And he raises difficult questions about what the decline of a free press means, not just for journalism but for Australian democracy.

Reviews

Read what the critics said below.

My dear Ben,

Reading your splendid book (online, bought it on Kobo). Would like to say I am enjoying it, but that’s not the word. It provokes disgust and despair.

But well done, it’s terrific (I smiled at your portrait of Robert Haupt, a friend and co-conspirator).

How lucky we are to have enjoyed the years of milk and honey before it all soured.

– Mike Carlton, Fairfax columnist and former broadcaster

Thoroughly researched, well written, very incisive.

– Phil Ruthven, founder and chairman IBISWorld

Stop The Presses is a triumph… Yours is the definitive account, placed in a bigger, socially relevant context. You’ve told the story with acuity, energy, style and humanity.

– Shaun Carney, former associate editor of The Age

Congratulations on a far more informed and balanced recent history of Fairfax than some recent efforts.

– Lloyd Whish-Wilson, former Fairfax Media Publisher and Chief Executive (NSW and ACT)

Whom the gods wish to destroy…

Ben Hills offers a distinctive take on what went wrong for Fairfax, writes Ken Haley

Manufacturing in Australia is not doomed so long as there are theories to be constructed (and published as books) about the decline and fall of the once-mighty Fairfax newspaper empire. As that kind of empire goes, Fairfax can make a couple of claims none of the others can. It is the oldest survivor of the era of family-run newspapers, and its flagship Sydney Morning Herald (founded 1831) is the oldest continuously published newspaper in the southern hemisphere. The higher they fly, the harder…

A flurry of book-length attempts at explaining the company’s slow-motion implosion has appeared in recent years, the most notable until now being Killing Fairfax, by Australian Financial Review reporter Pamela Williams. That 2013 paperback was subtitled “Packer, Murdoch & the Ultimate Revenge,” in a nod to the complex causes that turned the Age, once regularly referred to as “one of the world’s great newspapers” into a shrinking compact remnant of its old Leviathan self.

In those glory days, senior executives were proud of the paper’s global reputation for excellence but still able to puncture any pretensions of grandeur with a well-aimed shaft. This reviewer, who worked for the Age at the beginning of the 1980s when its daily circulation exceeded 250,000 – a record unequalled in its 160-year history – recalls ripples of mirth spreading among the staff on hearing that deputy editor Peter Cole-Adams had picked up the phone at the paper’s then lavishly staffed London bureau and satirically intoned, “Good morning. You’ve reached the Age, one of the world’s great newspapers.”

Williams’s work treats the humbling of Fairfax as a sort of manslaughter mystery: no one set out to murder the Old Firm but, when it comes to whodunnit, everyone seems to have given Fate a helping nudge.

Hot on its heels comes the latest investigation of this media giant’s comeuppance, from the acerbic pen of former Age wunderkind and Sydney Morning Herald super-correspondent Ben Hills, whose warts-and-all portrait of his former boss, legendary Age editor Graham Perkin, appeared in 2010.

Hills, too, resists a simplistic “It was Wokka wot dunnit” explanation, although he does give due emphasis to the reverse-Midas touch of Young Warwick Fairfax in the late eighties. The culprits Hills fingers in the subtitle of his book – “How Greed, Incompetence (and the Internet) wrecked Fairfax” – are a motley crew. Yet the tale he tells of how they interacted to hasten the hollowing-out process is not only credible but convincing.

Acknowledging “the competition,” Hills promises in his prologue to provide more than a mere historical account of corporate downfall. It is a promise largely redeemed in nearly 400 pages that see the author move from boardroom fly-on-the-wall to social commentator, and even to rural reporter. For it was not just the celebrated mastheads of big-city titles that were lashed by a perfect storm of hostile elements: the smallest, most remote outposts of empire also came tumbling down.

It is Hills’s gift as a reporter capable of adding the human dimension to his description of a powerful institution’s first intimations of mortality that lifts Stop the Presses! above the ruck. His shoe leather can be heard pounding the pavements of Cobar, in northwest New South Wales, as he discovers the damage done by the felling of Fairfax to the least of its far-flung family.

The occasional quirky turn of phrase can be jarring. At one point, Hills writes of “Asia and India” as if the latter weren’t part of the former. Equally occasionally, an omission grates. Robert Whitehead is mentioned as a Fairfax marketing guru but he, too, occupied the editor’s chair at the Sydney Morning Herald, which surely rated a mention.

Far more often, though, Hills’s impish sense of humour provokes a laugh out loud. One of his many sources, former Herald business editor Ian Verrender, recalls trudging into the boss’s office to take his redundancy after half a lifetime with the company. The editor-in-chief, Sean Aylmer, “sprang forward with his hand outstretched and a big smile on his face crying, ‘Congratulations!’ as though he had just won a holiday for two in Bali.”

The more I read, the more I found myself thinking Fairfax is like a patient who doesn’t realise he is dying despite every new day (or at least every financial year) bringing a new and grimmer prognosis. It wasn’t Aylmer alone who failed to comprehend what was happening. From Fred Hilmer, whose appointment as CEO may, unknown to himself, have been a piece of Machiavellian foreplay by one Kerry Packer, to Greg Hywood the downbeat optimist, the Grand Old Publisher increasingly resembles an invalid who has lost the will for yet another bout of “life-saving” surgery.

Inevitably, many of Hills’s sources and dramatis personae also appeared in Williams’s narrative. One by one we meet the various scions of the Fairfax clan and watch it unravel because of shortcomings ranging from internecine jealousy to reckless inattention. There goes Ron Walker, who claims the moral high ground in giving rapacious Gina Rinehart the keys to the kingdom but comes across more like a Trojan horse than a knight in shining armour; here comes Roger Corbett, whose distaste for bringing in expensive consultants to tell newspaper managers how to manage is a familiar theme, but nonetheless refreshing.

If Fairfax management were reminded of that view once in every book likely to be written on its failure, it would still be worth hearing. Had it been heeded, of course, there would be no market for this offshoot of Australian manufacturing, a growth industry in rough drafts of the history of how the Fairfaxes, who for forty years repeatedly had the winning hand in the hold ’em poker game of quality journalism, ended up losing it all and cashing in their blue chips.

The oft-cited observation “Whom the gods wish to destroy they first make mad” is variously attributed. But, pace Porgy & Bess, it ain’t necessarily so. With apologies to Longfellow (and perhaps Sophocles), Ben Hills’s fine-grained study of this modern-day epic tragedy lends itself to the suspicion that in certain cases the gods prefer to make them far too comfortable, careless and greedy for their own good.

– Ken Haley, Inside Story, August 7 2014. Ken Haley tutors in journalism, media and politics at Swinburne University of Technology. He was a Walkley Award–winning journalist for the Sunday Age and is the author of two books.

Read and weep at Fairfax’s downward spiral of incompetence

By Mark Day

FORENSIC analysis of the decline and decline of the once-mighty Fairfax media empire has become quite an industry. Colleen Ryan and Pam Williams, both former Fairfax journalists, have written books about it and now we have Ben Hills mining the same deposits of what he calls greed and incompetence.

He comes up with some gems, pulling together a racy story of the characters and their calls that have seen Fairfax’s fortunes plummet alarmingly over the past three decades.

It is, in many ways, a tragedy and it is, like most tragedies, built around human error, human frailties and rampant egos. It’s a racy read, as you would expect from a newspaper pro skilled in digging and sifting mountains of material.

The focus of Hills’ 374-page hardcover book Stop The Presses (ABC Books) is Fairfax and its mismanagement, but the wider agenda is not limited to Fairfax. The issues at stake — the disruption of a once-powerful publishing industry by the internet and the shape and financial structure of what replaces it — are global in their scope.

Hills does not to leave the reader with any sense of what is next for Fairfax. We know the rivers of gold are now dry gulches; we know the day will come when the once-fabled jewels, the Sydney Morning Herald and The Age are printed no more; but what then? What is left? A costly news website, a real estate site and a dating service? Sir Warwick Fairfax would turn in his grave.

Ben Hills joined Fairfax’s Melbourne flagship The Age in 1969 when it was still owned by the Syme family and he spent more than 30 years with the company as an investigative reporter and foreign correspondent. It is fair to say he served during the golden years of print.

In his account, Hills is kind to Greg Gardiner, the former merchant banker who became managing director in 1980 and drove revenues to $1 billion by 1987 when The Age published a world-record size Saturday edition of 242 broadsheet pages, weighing nearly 2kg.

But the rot began on Gardiner’s watch. He was spooked by the fallout from Paul Keating’s 1987 “princes of print and queens of the screen” legislation and against the then rules, against advice and against all common sense he overpaid to buy Melbourne’s Channel 7 before selling it and Fairfax’s other TV assets in Sydney and Brisbane to Christopher Skase on deferred terms — which led to a loss of a cool $200 million.

Gardiner’s stewardship so alarmed Warwick Fairfax Jr, the 26-year-old son of former chairman Sir Warwick Fairfax that he decided he could no longer wait for his inheritance — he had to buy it now. Just before the share market crash of October 1987 he bid $2.3bn for the company in a leveraged buyout — the first step towards bankruptcy three years later.

Hills exposes the madness of the following years when the rapacious Conrad Black took control but he reserves his most biting criticism for Fred Hilmer, the risk-averse management professor who took over as Fairfax CEO in 1998.

Hilmer described journalists as “content providers” — a sure signal that he had not a clue about the creative forces behind the products his company sold. He didn’t read newspapers, had never been an executive and had no interest or experience in media. Hills says Kerry Packer called Hilmer “the most intelligent f. kwit I’ve ever met.”

Hills’ thesis is that Hilmer missed the internet boat when it began to erode the huge classified advertising business at Fairfax. I’m not sure that is true because he set up a separate digital division called f2, but I don’t argue with the proposition that Hilmer’s response was conceptually wrong and woefully executed.

The most experienced journalists and executives on the traditional newspaper titles were shut out of f2 as it embarked on massively costly projects like City Search — akin to Fairfax trying to out-Google Google in the creation of digital answers to questions like “where can I get a good cup of coffee.” City Search had cost more than $100 million when it was sold for $20m.

The f2 business was the exclusive fiefdom of Hilmer appointee Jack Matthews, a Canadian who decreed that SMH and Age journalists would have no influence over the news websites that carried their mastheads. It was an extreme folly — while the newspapers followed their upmarket paths, their websites descended into click bait gossip and nonsense.

Hills also aims some blows at CEO David Kirk and his then chairman Ron Walker who embarked on a buying spree to bulk up the company. They took over Independent Newspapers in NZ — an amazing purchase, given the context: more legacy mastheads at a time when they were clearly threatened, if not dying. They did it again with the merger with Rural Press which managed to blow up a billion dollars for young Warwick’s cousin, John B Fairfax. And they saddled Fairfax with mountains of debt which succeeding directors have felt they had to retire — by selling profitable, viable digital assets such as the Trade Me website and Stayz, an accommodation booking business.

Item by item, Hills describes the downward spiral of Fairfax. It makes a devastating picture of a company incompetently mismanaged. But it is a story without an end because the end is not yet in sight.

CEO Greg Hywood has taken tough decisions to rip hundreds of millions of dollars out of the business. In time, this may be seen as merely slowing the rate of decline. But despite many attempts at weaving a confident “onwards and upwards” spell over Fairfax, Hywood has not come close to outlining what he sees as a viable future business model. We all understand the need to lower the cost base and when that is done, lower it more. We accept that when the presses stop the costs of production will fall by half a billion a year.

But what will be left? As Crikey owner Eric Beecher tells Hills: “There is no business model. When the papers go online they will have to decimate their editorial cost base … rip it to shreds. They are going to have to get rid of two thirds, maybe 90 per cent, of their staff. There’s no funding source for them online. It just doesn’t exist.”

Read it and weep.

– Mark Day, The Australian, 18 August 2014

In Short: Non-Fiction

When the ‘‘dog killer’’ editions of The Age and The SMH disappeared it signalled a seismic shift in the newspaper industry: the classifieds – the so-called ‘‘rivers of gold’’ – had dried up and, largely, gone on-line. As this sobering study of Fairfax shows it’s not the only reason the company, and newspapers in general, face a challenging future. Fairfax, Ben Hills maintains, made serious blunders, ill-fated and expensive ventures such as new printing sites and reacted slowly to the threat of the internet, among other things. This is an informed – Hills is a former Fairfax journalist– often fly-on-the-wall examination of the cut-throat world behind headlines, written with flair and not a little regret. The dogs are happy, but no one who values a free, independent press should be.

– Steven Carroll, The Sydney Morning Herald, 16 August 2014

This is what Ben says about the book in his preface:

Tackling a book about the death of the industry where you have spent your life is not unlike being asked to write your parents’ obituary. Newspapers, particularly the Fairfax newspapers, have been my life since I began work as a teenaged cadet on the midnight-to-dawn shift at the long-defunct Sun in the 1960s. I stepped back from fulltime journalism in 2007, which, ironically, was the year a few of the thousands of newly-unemployed American journalists set up the grimly-titled website newspaperdeathwatch.com. Today that site lists 272 newspapers, a dozen of them major metropolitan dailies which had served their communities for more than a century, which have gone out of print in the past decade. This book sets out to ask: will Australia’s two greatest and oldest newspapers, The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age, be the next to succumb? Will Sydney and Melbourne, which a generation ago had four daily papers, become one-newspaper, or even none-newspaper towns? Who is responsible? And what will it mean to the public?

It is too easy, and too obvious, to put all the blame for the collapse of circulations and revenues of the Fairfax Media papers on the internet. True it is that the Herald and The Age, more than probably any other papers in the world, depended on what Rupert Murdoch once drooled over as “rivers of gold” for their profitability, the huge revenue streams from the hundreds of pages of classified advertisments they carried. And those rivers have now run dry, drained off by the new, cheap, slick online marketplaces for real estate, employment and cars, “pure play” electronic brokers without the huge costs of maintaining printing plants and newsrooms with hundreds of journalists. You would have to have spent the last few years in a cupboard not to know this.

So what? There is hardly an industry which has not been impacted by the internet, from struggling city department stores to record companies, from universities to book-publishers, from fixed-line telephony to travel agents, film cameras to ‘snail mail,’ from adult shops to law firms to the shuttered suburban stores which once hired out CDs and videos. Free-to-air television will be next as IPTV rolls out with the national broadband network. It is what management gurus call a disruptive technology of the sort which comes along perhaps once or twice in a century — Caxton’s printing press in the 16th century, Isaac Newton and the birth of science in the 17th, Jethro Tull and the agricultural revolution of the 18th, electricity and the steam engine in the 19th, the internal combustion engine, air travel, telecommunications, broadcasting and the computer arriving in a rush in the 20th. Farewell town-cryers, cart-horses, sailing ships, whaling (for the oil, for the lamps), sedan chairs and stage-coaches, telegrams and typewriters. And now along comes the internet to turn everything on its head once again. Tomorrow the printing press and the daily paper will take their place in museums and libraries, another quaint anachronism from a bygone age.

And yet newspapers are different. For 300 years they have been the way people find out about the world beyond their neighborhood. It is no coincidence that this spanned the West’s transition from rule by church, king and general to democracy. From Thomas Jefferson to, well, Malcolm Turnbull people have argued that democracy is impossible without free speech, without a prying press to hold those in power to account, to defend the rights of the individual against the state, to afflict the comfortable and comfort the afflicted, to debate the big questions and as Hugo Black — one of the great US Supreme Court justices of the 20th century — once said “… to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell.” And that was long before Iraq. If you need further proof of the importance of a free media look at any military coup — the first thing the generals do is seize the TV station and jail the newspaper editors.

A lot of media people who should know better argue that the internet does not spell the end of the newspaper, just its long-overdue transition from crushed-up trees to an electronic signal on a screen. For a while Fairfax took comfort from the fact that even as its circulation plummeted its “mastheads” had more readers than at any time in the papers’ history — four times as many people accessing them online as in print. That was when they were giving their content away for nothing. Now that they have decided to charge for access, the audience has shrunk dramatically. But this is not the point. It is not a lack of readers that is killing the papers. It is a lack of money. The classified advertisments have long gone, migrating like swallows to the warmer climes of the new internet companies. Newspapers have managed to attract only around 10 cents-worth of online advertising for every $1 they have lost in print, and there is no way a $25-a-month digital subscription will make up the difference, unless you happen to be a global brand like The New York Times. Ninety per cent of what had been Fairfax’s main source of income for the last 200 years has disappeared forever. Ninety per cent of the money needed to run those great newsrooms has gone.

After hoping for years that the problem would go away, treating it as a temporary downturn in revenues that could be remedied by yet another round of cost-cutting, Fairfax finally bit the bullet in mid-2012, and decided to sack one in five of its 10,000 workers, shutter its vast, obsolete printing plants and become a “digital first” news provider. Out the door went hundreds of my former colleagues in the greatest diaspora of journalistic talent this country had ever seen. The papers shriveled in both quantity and quality, outsourcing their sub-editing, amalgamating their newsrooms until they came to resemble one newspaper with three mastheads. But why had the company taken so long — nearly 20 years — to realise what an existential threat the internet posed to its business? Why had successive generations of management and boards of directors been so wilfully blind? Why did Fairfax not meet the threat head-on by launching its own internet sites, or by taking over the fledgling rivals which would, within a few short years, dwarf Fairfax in size and profitability? These are some of the questions I set out to answer.

This is not just a book about mismanagement on an epic scale destroying one of Australia’s greatest and oldest institutions. It is not just a book documenting the decline and fall of what was once Australia’s premier media company, with its empire of hundreds of newspapers, magazines, TV stations and a radio network serving an audience of millions. It is both of those and it is more.

Above all, I have tried to tell the story of the people involved in the disaster, through their own eyes, in their own words. The fat-cat directors with no knowledge of the newspaper industry, whose foolish feuding squandered opportunity after opportunity. The heirs to the Fairfax family fortune whose attempt to reclaim their heritage instead contributed to its downfall and cost them a billion dollars. The predatory moguls, the Packers, Murdochs and Stokeses, circling like dingos in the darkness just beyond the campfire, waiting for their chance to pounce on the prey. The procession of chief executives, caught like deer in the headlights, whose only plan to meet the challenge of the new technology was to cut, cut, cut. And when that didn’t work to call in the management consultants. And when that didn’t work to call in some more. The pension fund managers, proxy advisors, share-shorters and the other faceless powerbrokers manipulating the share-price and pulling the strings from behind the scenes. The hundreds of journalists, photographers and printers who, having given their lives to a company which still, at least at The Age, dishes out gold watches for those with 25 years’ service, found themselves discarded on the scrap-heap. The people of little outback towns who were suddenly, at the stroke of a pen by a faraway bean-counter, without the paper that had chronicled their communities for more than a century. You will meet all these, and many more.

I write this with as much sadness as anger. Yes, there is anger that the people of Sydney and Melbourne are going to lose the papers that have served them since the days of the convict, the sailing-ship and the gold-rush, to be replaced by an online wraith. Anger that one man’s folly delivered to a market interested only in short-term profit an institution as fundamental to a fully-functioning society as the Fairfax papers. Anger that a board, arrogant in its ignorance, and its incompetent executives could cause so much pain and grief. But there is sorrow, too, at the recognition that no matter how smart the strategy, how savvy the managers, it might have all ended in tears anyway. So pitifully few great newspapers anywhere in the world have made the transition from print to the internet without sacrificing the very things which made them great.

Within a few years the age of the printed newspaper will be over, and the Fairfax company — if it survives at all — will be unrecognisable. By the middle of 2014 Fairfax’s fortunes had made a modest recovery from their lowest ebb, although the company’s share-price still languished at less than one fifth of what it had been at the height of the media bubble more than a decade before. The recovery was due not to the success of its newspapers, which were still bleeding revenue and circulation apace, but to its transformation from a news organisation to an hodge-podge of online businesses. The Fairfax of the Future will be an eclectic combination of real-estate spruiker, lonely hearts matchmaker, baby goods retailer, organiser of food fairs and promoter of fun-runs, ocean swims and soirees showcasing business moguls. With, somewhere in a back office staffed by work-experience youngsters, some kind of stripped-back online news service, bereft of its foreign bureaux, its lifestyle sections, its magazines, its photographers and most of its best writers.

I had my lifetime during the golden age of newspapers. The people I feel sorriest for are those left to labour bravely away among the ruins. As one very senior editor told me: “Mate, I was born 20 years too late.”

Publishing Info

Stop the Presses – How Greed, Incompetence (and the Internet) Wrecked Fairfax, was released on 30 June 2014, published by HarperCollinsPublishers Australia.

Excerpts were published in The Australian the previous weekend, and the paper’s Media section described it as a “must read.” There was extensive media coverage.

Interviews

Ben spoke with various journalists about his book:

ABC, 21 July 2014

Ben Hills joined John Faine on ABC’s the Conversation Hour to discuss Stop the Presses!

Listen here >

The Perrett Report, 12 July 2014

Ben Hills talks with Janine Perrett and Mark Day from The Australian about the future of newspapers. Watch here >

Mediaweek, 11 July 2014

Ben Hills talks about his new book with James Manning, Mediaweek Editor and Brenden Wood, Syndicated Media Commentator.

666 ABC Radio Canberra, 7 July 2014

Ben Hills joined Genevieve Jacobs on 666 Mornings to discuss Stop the Presses!

Listen here >

The Bolt Report, 6 July 2014

Ben discusses the book with Andrew Bolt on Channel Ten’s Bolt Report at 8.15 am on Sunday 6 July 2014, from 33 mins 27 secs. Watch here >

ABC Radio, 30 June 2014

Ben was interviewed by Mark Colvin on the ABC’s PM programme on June 30 and on ABC news and current affairs programmes in Newcastle, Brisbane, and Canberra.

ABC Radio Brisbane, 30 June 2014

Ben Hills joined Steve Austin in studio to discuss the decline of the Fairfax media empire.

Listen here >

crikey.com.au, 30 June 2014

Stop The Presses is, at heart, a story of Fairfax’s board over several decades, and how it got it so wrong. Full of the corporate intrigue and no-holds-barred sledging, here’s Crikey’s guide to the juicy bits. Read more >

The Australian, 23 June 2014

Stop the Presses, is a “must-read” — Sharri Markson, Media Editor, The Australian. Read more >