Ben Hills

Not long after being sworn in as one of parliament’s new intake of MPs, Ken Wyatt decided that it was time to give the leader of his party a complimentary character reading.

Tony Abbott had launched Wyatt’s campaign (for the seat of Hasluck, on Perth’s southeastern fringe) a few months earlier. But they had only met on a handful of occasions. Wyatt was not one of the PM’s inner circle.

Undeterred, he felt he had to speak up. He asked the Liberals’ chief whip, a knockabout North Queenslander named Warren Entsch, to arrange a meeting. When Abbott arrived, his new backbencher – to his surprise – proceeded to lecture him on his failings.

He needed to learn to listen, Wyatt said. He had a problem with women. The list went on.

“I noticed his absolute anger with me,” recalls Wyatt. “I said ‘I know I’m pissing you off, but I just want to share this with you, because I believe you’ve got the capacity to be a great leader.’”

“Listen to him, Tony, because he’s a blackfella [and] when they tell you something [they mean it].”

Entsch chipped in: “Listen to him, Tony, because he’s a blackfella [and] when they tell you something [they mean it].”

Abbott folded his arms tightly, turned on his heel and stalked off, fuming at the effrontery. For a “newbie” MP, it was not a good career move. It would not be the last time he and his leader crossed swords.

When I ring Entsch at his electoral office in Cairns, he confirms the story.

“At the time, I thought ‘You cheeky bugger’,” he says. “But Tony ignored him at his peril.”

“He should have listened. He should have made the effort to change, because it played a part in his downfall. It’s part of the reason Tony is no longer with us.”

That was in the aftermath of the cliffhanger election of 2010, when Abbott failed by a handful of votes to unseat the government and Julia Gillard cobbled together a coalition to keep Labor in power. Today, Abbott is gone, deposed as Liberal leader and reviled by some as the worst Prime Minister Australia has had since World War II.

What did Ken Wyatt think of Tony Abbott? What are his plans now?

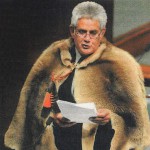

Ken Wyatt has been vindicated, after languishing for five years on the backbenches, by being elevated to Malcolm Turnbull’s ministry: the first Aboriginal minister in the 114 years since Federation.

His election made news around the world, particularly when he rose to his feet to make his maiden speech in the House of Representatives, his shoulders draped in a traditional cloak of kangaroo hide, decorated with the feathers of a red-tailed black cockatoo.

The applause of the House would have drowned out the memory of the racist taunts spoken to his face and posted online, of which one of the more printable read : “For Christ’s sake, coon, wake up. All of us true Australians (the white ones) know you lot are just feral savages. You don’t have to go round bragging the point.”

“How does it feel to be the first Aboriginal person elected to the parliament of the most racist nation in the world?”

The BBC can be forgiven for ringing from London to ask him, in effect: “How does it feel to be the first Aboriginal person elected to the parliament of the most racist nation in the world?”

His appointment as Assistant Minister for Health after this year’s “September Surprise” was a story that wrote itself: the barefoot kid from the bush, a child of the Stolen Generation, one of a family of 12 who trapped rabbits to put food on the table, now with a hand on the tiller of the ship of state, an office in Canberra, staff and a $275,000 salary.

Shattering the “brown glass ceiling”, as he puts it. Some achievement for a man whose parents’ generation could have been jailed for drinking, and who – until the 1967 referendum – were not even counted in the census, but listed along with livestock when properties were put up for sale.

“I wouldn’t have voted for you if I’d known you were an Aborigine.”

The story begins in Nannine, a railway fettlers’ camp near Meekatharra in Western Australia’s remote and arid mid-west, which is now a ghost town.

Like many of his generation, Ken Wyatt is a potpourri of ethnicities: grizzled grey hair, a tanned complexion and a bulky body he struggles to keep in check. His wife jokes that when they visited her family in Italy the only words of Italian he learned were “basta pasta” (“enough with the pasta”).

He seems amused at the confusion of a constituent who told him after the election: “I wouldn’t have voted for you if I’d known you were an Aborigine.”

When he visited the Middle East, a taxi-driver told him he looked Arabic. In fact, his mother, Mona Abdullah, gets her surname from an ancestor who migrated from India to be a cameleer, laying the trans-Australia telegraph line. She has both Noongar (Ken’s tribal robe) and Wongi bloodlines. His father, Donald, nearly two metres tall and built like an ox, was from the Yamatji people. There is also some Irish and English in the family tree.

According to files from the Native Welfare Department, which Ken tracked down many years later, Mona had grown up with other “half castes” in Roelands mission farm, inland from Bunbury in the state’s southwest. She and her nine brothers and sisters had been taken from their parents as children – part of a eugenic policy to “breed out” their Aboriginality – and scattered among three different missions, hundreds of kilometres apart.

In her teens, she was sent to work as a domestic servant on a property near Nannine and there she met Donald, a railway fettler, possibly at a race meeting. Their first son was born in Bunbury Hospital on 4 August, 1952. Ken was taken back to the dusty hamlet of Nannine, where he spent his first seven years. His only education was the School of the Air, which he accessed via a crackly pedal-driven radio.

His real education only began when the family moved to the Big Smoke, the town of Corrigin (population 903) in the wheat belt, 229km southeast of Perth. There the gawky, shy young lad was taken under the wing of the local community. His first teacher, Lynne Abernathy, gave him half an hour’s one-on-one coaching every day before school, a start in the life of the mind he never forgot.

When she turned up to hand out how-to-vote cards for his election 50 years later, he presented her with an apple, a gift he had never been able to afford when he was her student.

“This bloke is going to go places. My only disappointment is that he went for the bloody Libs.”

“He was a smoothie, a real smoothie,” recalls Ken Wyatt’s one-time head teacher at Corrigin. Now aged 88 and living in retirement in Perth, Alan Jones says of Wyatt, “Scholastically [he] wasn’t exceptional, but he was a lovable bloke, someone you really warmed to, and even at 15 he had an authority about him.”

“I reckoned ‘This bloke is going to go places’. My only disappointment is that he went for the bloody Libs. I’m a Labor man myself.”

Wyatt repaid the attention by studying hard and reading anything he could lay his hands on at the library and the local church: everything from Mark Twain, to Aristotle, to The Cross and The Switchblade, the inspirational autobiography of a New York street pastor. Rather than being sneered at as a swot, he was so popular with his classmates that they voted him head boy in his final year at school – his first electoral success.

By now, there were 10 children, all living in a small fibro government house near the school.

“There wasn’t a lot of money,” says Ken’s brother David, 13 years younger than his famous sibling. David lives in Merredin, where he works as a train driver.

“And we did have a lot of prejudice against us, especially on the sporting field. But Dad always used to say, ‘Turn the other cheek. Life is what you make of it, whether you are black, white or brindled. Educate yourself. Knuckle down and apply yourself.’”

But it was a hard life. Two of Ken’s younger brothers died young, of cancer – one with a terrible case of mesothelioma, contracted from asbestos.

At 4:30am on a bicycle, with a .303 rifle over his shoulder, he would check the rabbit traps.

Ken’s idea of knuckling down was to get work, to help out with the household – any work he could find. He would get up at 4:30am and set off on a bicycle with a .303 rifle over his shoulder (in case he encountered a fox), to check on the rabbit traps he set. Any surplus bunnies he would sell to the local butcher.

He drove around with Roy Hansen, his music teacher, collecting empty bottles for the deposit, to pay for recorders and a drum kit for the school band. He went fruit picking, he worked as a labourer on building sites during school holidays, he put up fencing from sunup to sundown for $2.50 an hour, he worked as a rouseabout in a woolshed and plucked stones and mallee roots from paddocks prior to ploughing.

If they understood the enterprise he showed as a kid, his family – most of whom are dyed-in-the-wool Labor voters – and friends would be less surprised that Ken turned to the Liberals.

Living across the road from the Wyatts was David Jones, a local builder and pillar of the Rotary Club.

“They had no money, I don’t think they even had a car, and Ken’s dad used to hit the bottle a bit,” he recalls. “But Ken became mates with my two boys and I used to drive them around to sporting events.”

So impressed were Jones and his teachers with his potential that they decided, in Ken’s words, “This young fellow’s too bright to just let him work on a farm”. The Rotary Club, the Country Women’s Association and other benefactors “adopted” Ken and raised the money to send him to Perth, to finish high school.

Memorable moment for a younger Ken Wyatt.

His first job after he matriculated didn’t end well. He went to work at the Land Titles office and found himself responsible for collecting land tax. One day, he was told to resume the properties of three Italian orchardists from Donnybrook, who had failed to pay their taxes.

“I’ll always remember this one guy who came in,” Wyatt says. “I got his file and I showed him all the letters we’d sent, and he said ‘I can’t read’. I then had to say ‘I’m sorry, we’re going to have to take your property.’”

“The guy really broke down, he just sobbed. And I just thought ‘No, I don’t want to do this to people.’”

That was a turning point in Wyatt’s life. He took up a scholarship, went to teacher’s college for two years, and when he graduated he began a career as a primary school teacher.

By then, aged just 21, he had married. His first wife, Roza Veskovich, was the librarian daughter of Balkan immigrants. Their first home must have been quite a surprise: it was a funeral parlour. Actually, it was a flat above the Bowra and O’Dea funeral parlour in East Perth. Their bedroom opened onto the area where the coffins were stored.

For the four years they lived there, the young couple were paid to be the nightwatchmen. It was quite a learning experience.

“The police would ring and say ‘The Bon Marche arcade, the jeweller there has been stabbed to death. We need to get the body down to the morgue,’ and we would have to organise it,” recalls Ken matter-of-factly. “It was a great time.”

“Not only did we learn about burial rituals, but [about] the dynamics of death and the effects of grief on the family.”

He remembers consoling a woman whose grandson had been swept out of her hands by a car on the way to the shops, as well as relatives of a young doctor at Geraldton who pulled his car over with a flat tyre and was killed by a truck, and of a 10-year-old child who had hanged himself. It taught him, he says, to be fatalistic: “We can plan for a long life, but let’s live each day and enjoy it, because you never know.”

Ken and Roza had two boys, Aaron and Brendyn, but after 25 years of marriage, they decided to separate. By then, Wyatt was a senior bureaucrat in Aboriginal health and education. “We grew apart,” he says.

“I was travelling every second week on national committees representing the agencies I had been employed in… With hindsight, I should have spent more time with my sons than I did. I always regret that, because you can never make up lost ground. Brendyn was aged 12 at the time… I’ll always remember him saying to me, ‘Come home’. Aaron was 14.’”

Whatever hurt there was at the time, Aaron at least is generous about his parents’ divorce. Now 33, he is a professional classical musician, playing violin and viola with orchestras – including the West Australian Symphony.

“It was a fairly normal childhood,” he says. “In spite of the fact that they split up, it was a fairly stable environment. The house was always filled with books and classical music. The ‘60s were really wasted on my mum. She was not interested in The Beatles at all.”

When he was young, he rejected being classed as Aboriginal and entered “No” on the forms he was handed at school – because he grew up in “typical suburbia” and there were no indigenous kids in his neighbourhood, or at school, with whom he could relate. But now he says he is proud to be one of only a handful of Aboriginal people trained in the classical music tradition.

By the time Wyatt was approached to enter politics, he was well-established in a new relationship – although they were not formally married until three years ago, when Ken was 60 and Anna 56.

She came from an Italian background – her family surname is Palermo and they come from a town called Caporio in the Appenine mountains, north of Naples. They met on the conference circuit – Anna works in indigenous education – and hit it off.

“He’s a lovely man,” Anna says. “Very humble, very gentle, he doesn’t big-note himself, he’s a good listener, he’s very… priestly.”

But she wasn’t keen on her fiancé going into public life. In fact, they had been planning a kind of genteel retirement, spending six months of each year in Australia and six months in Anna’s hometown in Italy. But it’s hard to say no to Liz Behjat.

Ms Behjat is a Liberal member of Western Australia’s Legislative Council and she had known Wyatt for years, through their membership of the same branch of the party in Perth. One day, early in 2010, they met at the opening of the Ngulla Mia mental health facility in Perth. She told him he had to run for preselection for the seat of Hasluck.

“I’d mentioned it to him before and he was humming and hah-ing about it… Anna wasn’t keen,” she tells me.

“Go and get a real job where you can make a difference.”

“I said to him ‘Listen, nominations close tomorrow. If you don’t nominate, you’ll never get another chance. With your talent and experience, you will floor the pre-selection committee. Go and get a real job where you can make a difference.’”

Wyatt protested that he already had a “real job” – he was WA’s Director of Aboriginal Health. But he went home and talked it over with Anna and that night, right on the deadline, he nominated. He rang Aaron who congratulated him, but said: “I can’t support you… what’ll I tell my mates at uni?” And, as Behjat had predicted, Ken Wyatt aced the pre-selection committee and won the nomination.

It’s impossible to tell what effect – if any – Wyatt’s indigenous background had on the vote. Hasluck is an ultra-marginal seat of nearly 100,000 people on Perth’s outskirts, where suburban housing estates melt into a green landscape of hobby farms, vineyards, and golf-courses. It had changed hands at every election since the seat was created, and Wyatt was up against a capable Labor incumbent.

He received 50 insulting letters, but for every bigot there are 100 Aboriginal voters.

For every bigot in the electorate (Wyatt received about 50 insulting letters and emails), there are 100 Aboriginal voters, but the vote was split because, extraordinarily, two of the other candidates were also Aboriginal.

In the end, there were fewer than 1000 votes in it. Hasluck was the last seat declared in the 2010 election after a nail-biting week of counting and recounting, and Wyatt just scraped home. He improved his vote at the 2013 election, with a 4 per cent swing, proving either that his background was now a plus or, more likely, that he had been a diligent local member.

The walls of his office are papered with his schedules for meeting constituents in his office (between a hairdresser and a pizza parlour in a suburban shopping centre), or at coffee shops and weekend markets. He paid particular attention in his electorate to “cleaning up the hoons on the zig-zag scenic route”.

Wyatt’s five years in parliament have shown that he is not just lobby fodder. After that first, confrontational meeting with Abbott, he has been prepared to take a stand on issues, even when they go against party policy. He threatened to cross the floor if the Liberals did not support plain packaging for cigarettes.

He complained about the arrogance of ministerial staff, long before Peta Credlin became an issue, after one staffer sat through a meeting looking bored and texting on his smartphone. “Backbenchers don’t matter here,” another told him.

“None of you will ever be vilified on the basis of race. None of you will experience the hurt.”

Last year, when the great debate was raging over changing the law prohibiting racial vilification, Wyatt says he stood up in the Liberal party room and told his colleagues: ”I just want to say something that I know will offend some people here. With the probable exception of six people, none of you will ever be vilified on the basis of race. None of you will ever experience the hurt… I am stating categorically that I will cross the floor (and vote with Labor)”.

Abbott backed down.

Says Wyatt’s friend and colleague Alan Tudge, the new Assistant Minister for Social Services (and Abbott’s former parliamentary secretary): “Ken is always very calm and there is a moral force about him. When he makes a contribution in the party room like that, people do listen to him. With hindsight, we overreached and stuffed up the politics.”

He crossed swords with Abbott once again after his leader was reported to have told a party meeting at a steakhouse in Alice Springs that he wished the party could endorse more “authentic” Aboriginal candidates, rather than “urban Aboriginal” people – a strange remark that Wyatt took as an insult, considering that most Aboriginal people, like him, are city dwellers.

When Abbott rang to apologise, Wyatt said: “Why is it that you question the heritage of an Aboriginal person? I’ve never heard you ask (Minister for Resources) Josh Frydenberg what percentage Jewish he is, whether he’s an authentic Jew. Or (Queensland MP) Teresa Gambaro what percentage Italian and whether she’s authentic Italian.” Ouch.

What does it mean to be a child of the Stolen Generation?

Wyatt has been less successful, however, with his push for something much closer to his heart – a referendum to recognise Aboriginal people in the Constitution. Five years since it was first proposed by Julia Gillard, the debate is still bogged down in consultations, with no clear path to a consensus and no timetable. The committee Wyatt co-chaired with the Aboriginal Labor Senator Nova Peris brought down its long-awaited report last June, recommending a new section banning discrimination on the grounds of race, colour, ethnic or national origin.

Wyatt protested that: “This is not about singling out Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island people or affording them extra rights above all other Australians. This is about correcting the contextual silence that is currently so deafening in the constitution.”

That is not the way conservatives in his own party saw it, however. They saw the proposal as a sword to assert new rights, rather than a shield to protect people and declared that it would transfer authority from the parliament to the courts. Aboriginal leadership is split on the issue.

The conservative commentator Paul Kelly wrote: “The cause is lost long-term. It means bipartisanship on indigenous recognition is a dead letter. [This] would achieve outcomes in public policy that neither the parliament nor the public will accept.”

There was a snippy exchange of text messages and a short, distinctly cool meeting with Abbott.

It was the final straw for Wyatt when Abbott failed to endorse his report and ignored a letter he wrote containing some new proposals, instead seeking a meeting with the Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson, who had been highly critical of the report. There was a snippy exchange of text messages and a short and distinctly cool meeting in Perth.

Wyatt had made his mind up – he was voting for a change in leadership.

His elevation to the ministry, at the age of 63, came as a complete surprise, Wyatt insists. Turnbull had never discussed it with him and he was not one of the coup plotters. He was pleased, however, not to get the Aboriginal Affairs portfolio. That, he believes, would have stereotyped him as only capable of dealing with Aboriginal issues.

He still remembers a senior bureaucrat deriding Aboriginal people in reserved positions as “Uncle Toms”. As Assistant Health Minister, he has been given responsibility for Aged Care, a job to which he says he is looking forward.

“Congratulations, Mr Minister. Now go and get the washing off the line.”

When he got his congratulatory phone call after he returned from an overseas trip, Anna was delighted: “‘Congratulations, Mr Minister,’ I said. “‘Now, go and get the washing off the line.’”

“You’ve got to keep ‘em grounded.”

Not that the new Prime Minister should expect blind loyalty from his independent-minded colleague, any more than the old one did. Although Wyatt has high hopes that under Turnbull, constitutional recognition of Aboriginal people will gain fresh impetus, there are other issues on which they disagree. He has made it clear that – like the leaders of 70 Aboriginal communities who sent the Uluru bark petition to parliament in August – he opposes same-sex marriage.

Unless there is a conscience vote on the legislation, Turnbull can expect a polite knock on his door and a gentle lecture from the man he made Australia’s first Aboriginal minister.

Publishing Info

Pub: SBS Online

Pub date: 23 November 2015

Photography by Grant Taylor

What did Ken Wyatt think of Tony Abbott? What are his plans now?